Meeting overload was a problem before the pandemic, but COVID-19 and the jarring transition to remote work have only made things worse.

Cut off from in-person communication, managers are overcompensating with even more team meetings. Only now they happen via video, which research shows — and anyone who’s been in back-to-back-to-back video calls can attest — are more mentally draining than in-person ones. There’s even a name for the phenomenon: Zoom fatigue.

Advice on facilitating better meetings is plentiful, but often skips a crucial first step: asking yourself whether you need to have a meeting in the first place.

Oftentimes, the most productive meeting is the one that never happened.

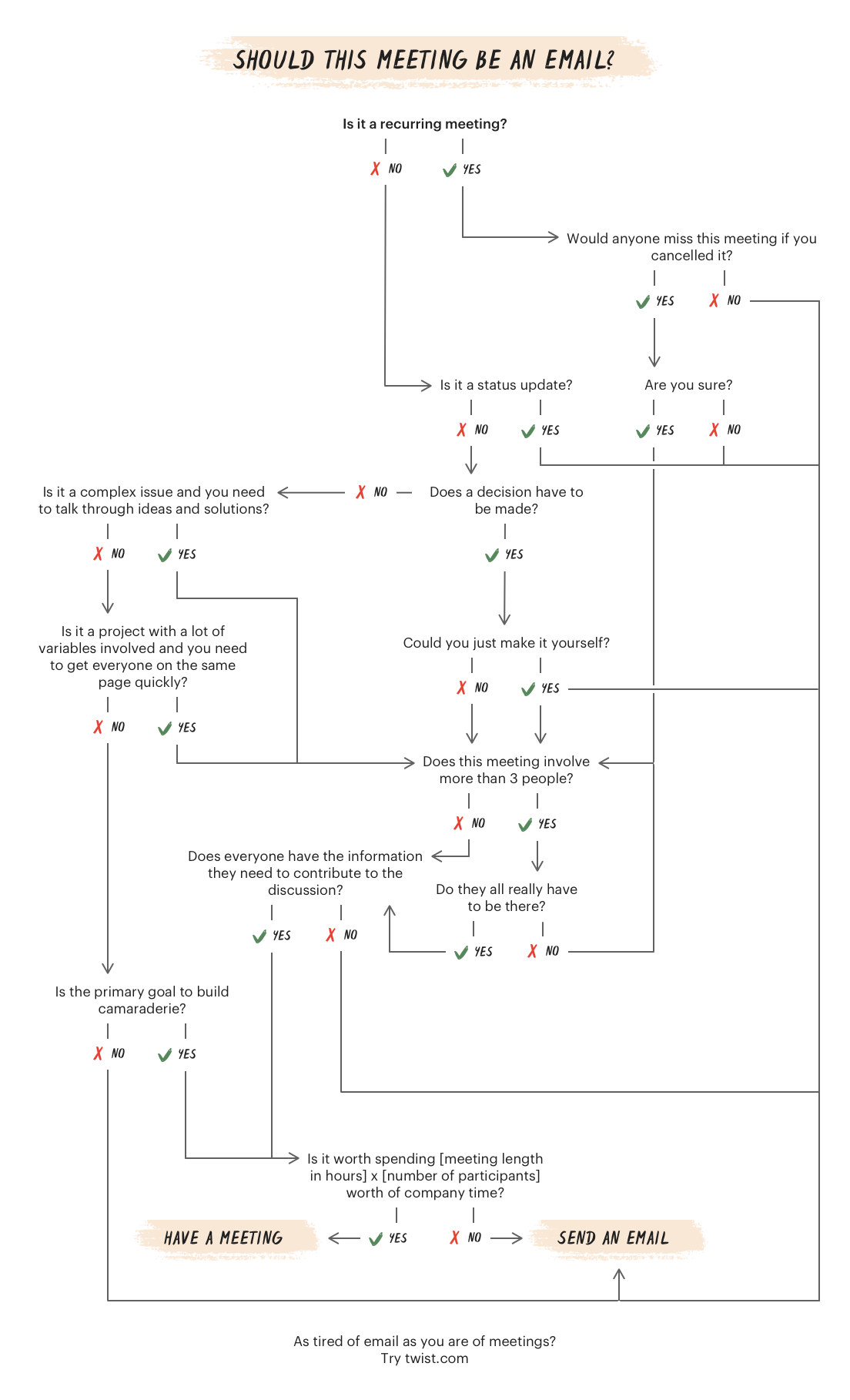

With that in mind, we put together a flowchart to help you decide whether to have a meeting or just send an email. We’ve also included a few tips for culling the meetings you have and minimizing the costs of the ones you decide to keep around.

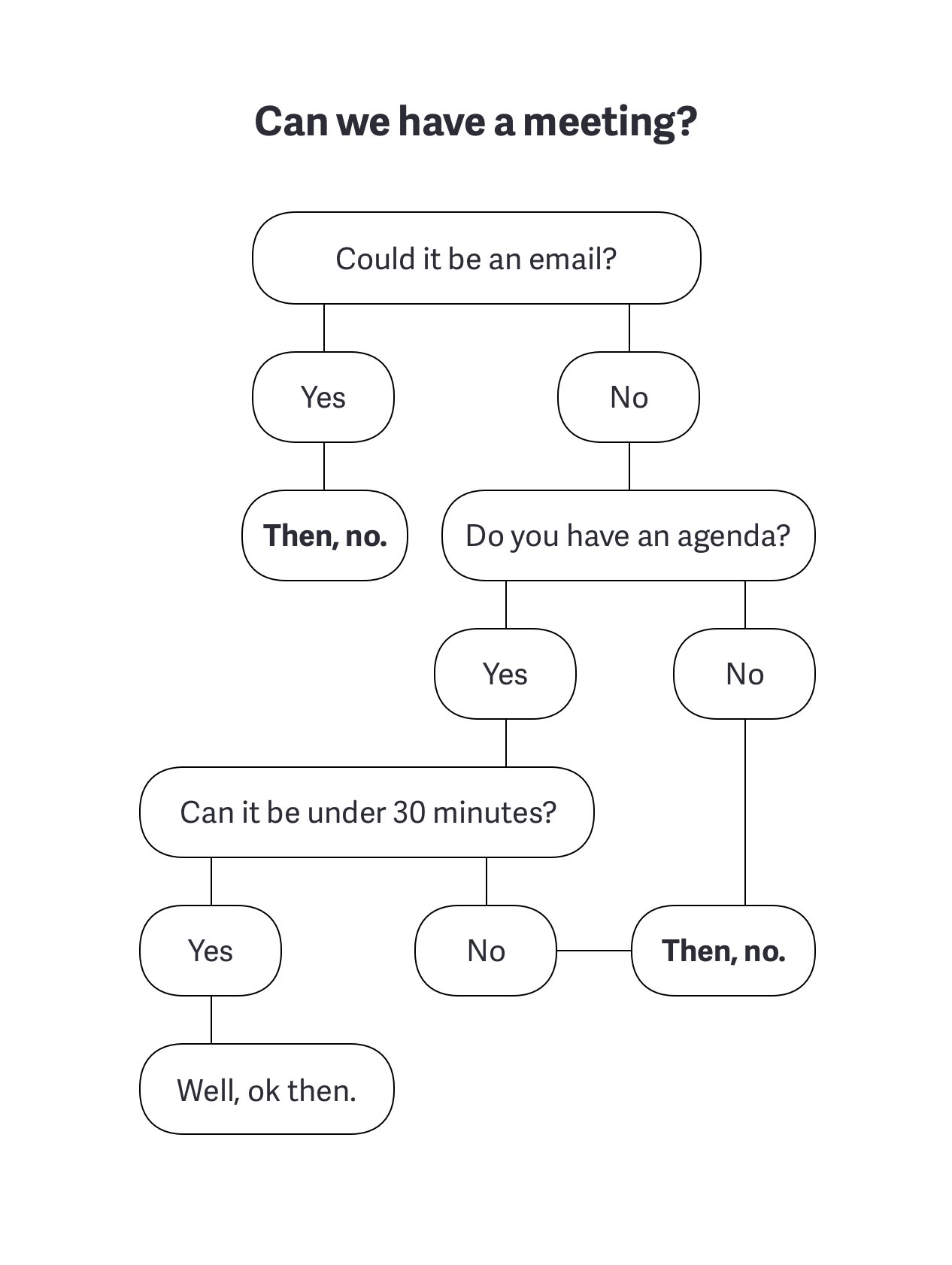

Are you on the receiving end of a meeting request? Here’s another handy flowchart to decide when to say yes and when to politely decline:

Here’s are a few additional tips for eliminating time-wasting meetings — or at least minimizing their impact on your team’s productivity:

Do the meeting math

Most people think a half-hour meeting costs a half-hour of time. It doesn’t. A half-hour meeting with ten people isn’t a half-hour meeting. It’s a 5-hour meeting.

Multiply that by how much your coworkers are paid per hour, and you get the dollar cost of the meeting.

You’d be surprised how quickly the bill adds up. A time study conducted by management consulting firm Bain & Company found that a single weekly meeting of mid level managers cost one large manufacturing company over $15 million a year!

Before you call a meeting, do the math and make sure it’s worth the time you’re asking for. Harvard Business Review even has a meeting cost calculator you can install on your phone.

Account for the meeting blast radius

The equation above is the absolute minimum cost of a meeting. It doesn’t account for the “blast radius” — the significant productivity cost of interruptions and context switching that bookend a meeting. The real equation should look more like this:

To complicate matters further, the productivity cost of context-switching isn’t the same for everyone. Paul Graham, one of the founding partners of the startup accelerator Y Combinator, distinguishes between two types of work schedules:

- The manager’s schedule: “The manager’s schedule is for bosses. It’s embodied in the traditional appointment book, with each day cut into one hour intervals. You can block off several hours for a single task if you need to, but by default you change what you’re doing every hour.”

- The maker’s schedule: “But there’s another way of using time that’s common among people who make things, like programmers and writers. They generally prefer to use time in units of half a day at least. You can’t write or program well in units of an hour. That’s barely enough time to get started.”

A half-hour meeting for a manager is no big deal. But for a maker, an ill-placed meeting can split the morning into two chunks, each too small to accomplish anything of substance. Before you know it, it’s after lunch and you still haven’t accomplished the most important things on your to-do list.

When deciding whether to call a meeting or send an email, be sure to factor in the full opportunity cost in lost productivity.

Declare “No Meeting Mornings”

One way to reduce the context-switching cost of meetings is to time block them. Instead of bouncing back and forth between work mode and meeting mode, separate your workday into two blocks: work time and meeting time (or maker time and manager time if you like). Block your work time off on your calendar, and don’t let people eat into it with meetings.

You might even declare a “no meeting” day of the week for a full day without interruptions. No Meeting Mondays has a nice ring to it.

If you’re a team leader, adopt “no meeting” times team-wide to help everyone bring more focus and intention to their workdays.

Limit meeting size to 5 or fewer

Studies show that small teams are more effective than large ones. Fewer people means that each person feels more accountable for contributing to the project.

The same logic can be applied to meetings. The more people involved, the easier it is for attendees to tune out. It’s much harder to social loaf on a call with four other people than it is on a call of ten or fifteen.

The cost of each additional person is even higher when you’re meeting virtually. Each added person increases the chances of scheduling conflicts, technical difficulties, background noise, and those inevitable awkward moments where two people try to talk at once.

While there are exceptions to every rule (e.g., “all-hands” meetings to promote team cohesion), very few meetings require more than five people.

Decline invites or leave if you’re not adding value

Just because a meeting is productive doesn’t mean it’s productive for everyone who’s there. And just because it’s productive for someone to be in a meeting doesn’t mean it’s productive for them to be there the whole time. How often have you had to sit through an hour-long meeting when only five minutes were actually relevant to you?

There’s an easy way to remedy these situations: Let people know it’s ok to decline invites if they don’t feel they’ll add value to the meeting, or to bow out in the middle of a meeting if it becomes clear their presence isn’t needed.

Here’s what Elon Musk says about the meeting culture at Tesla:

“It is not rude to leave. It is rude to make someone stay and waste their time.”

Beware of meeting creep

Just because a meeting is productive, doesn’t mean it will be productive forever. Many recurring meetings happen out of habit even after they’ve outlived their usefulness

Take all of your recurring meetings off the schedule for a week. Only add back in the ones that really were providing value you couldn’t get from sending an email or starting a thread. Do this on a quarterly or biannual basis to prevent meeting creep.

Adopt a writing-first approach

Meetings should be reserved for the activities that are best done face-to-face (or webcam-to-webcam): hashing out complex problems, making important decisions, talking through sensitive issues, coordinating projects with lots of interdependencies, etc.

In these cases, people should come to the meeting with all of the information they need to contribute. Jeff Bezos famously outlawed PowerPoint decks at Amazon meetings, instead requiring everyone to read 4 to 6-page memos (front and back!) that he said forces better thinking:

“The reason writing a ‘good’ four page memo is harder than ‘writing’ a 20-page PowerPoint is because the narrative structure of a good memo forces better thought and better understanding of what’s more important than what.”

At Amazon, executives spend the first 15 minutes of meetings silently reading these memos together, but there’s no reason they can’t be sent in an email or thread beforehand.

Your team will also automatically end up with better documentation of important processes and decisions that can be shared and referred back to later. Once a meeting is done, don’t forget to document the outcome for both accountability and future reference.

All of the advice around productive meetings can be boiled down to this: Before putting a meeting on the schedule, ask yourself “Is this worth interrupting my teammates’ time and attention for?”

Sometimes the answer is yes. Most of the time it’s no. Act accordingly.