How can we measure and improve employee productivity? It’s a daunting question that all managers face. But that wasn’t always the case.

We can thank a mechanical engineer named Frederick W. Taylor for our national preoccupation with workplace productivity.

In 1911 Taylor, a machinist and foreman turned management consultant, published a book called The Principles of Scientific Management. In it, he put forth the (at the time) revolutionary idea that production rested on variables related to men and machines.

Therefore, managers could — in a scientific and systematic way — optimize these variables to produce more outputs with the same amount of inputs.

In other words, businesses could make more money without any extra costs. You can just hear factory owners’ minds being blown.

They just needed to figure out the right ways to train and standardize employee actions. By fixing “blundering, ill-directed, or inefficient” human efforts through “systematic management,” individual – and by extension national efficiency – would rise, giving way to “maximum prosperity” for both employer and employee.

Of course, since the early 1900s our economy has undergone a profound shift from industry to the so-called “knowledge economy.” The emphasis on coal and steel has given way to software and intellectual property. Manufacturing-based employment has fallen from 33% of total U.S. employment to 10.7%. Knowledge workers make up nearly half of the overall workforce.

Yet Taylor’s manual work-based legacy lives on in modern management and leadership practices.

Countless academics, economists, business leaders, mathematicians, entrepreneurs, and productivity “hacking” enthusiasts have all tried in various (and sometimes weird ways) to increase individual and team productivity.

We take breaks for exactly 17 minutes every 52 minutes. We install performance-enhancing nap rooms and productivity-boosting juice bars in our offices. We set up tracking systems with timer and task lists apps.

We do all of this because we know optimizing productivity on an individual and team level is still important – vital, even – for businesses to thrive. (Hat tip to Mr. Taylor!)

The problem is, measuring employee output in a reliable way has become much more complex. We can’t just count the number of widgets coming off the assembly line anymore.

How can today’s leaders measure – and improve – productivity in a knowledge-based workplace? It turns out that companies have come up with some interesting and innovative solutions…

Where the Classic Productivity Tracking Model Fails Us

Consider the basic productivity formula: productivity = output divided by input. We want to know how much was produced (output) over a set period of time (input). And, more importantly, how we can increase output while holding input constant.

Simple enough, right?

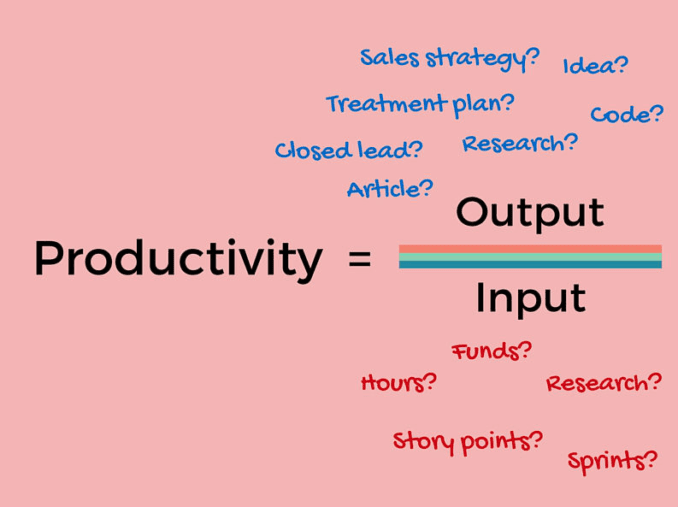

But unpack that idea just a little bit and cracks start to appear. What is being “produced” in a knowledge job? What is that output worth? Does time even matter? If so, when?

“When it comes to knowledge work, productivity is really hard to measure,” says Wharton Business School Operations and Information Management Professor Lynn Wu. “It’s nowhere near as simple as the number of bushels a worker picked in an hour.”

Traditional ways of measuring productivity fail us in a few key ways:

1. Quality is as important as quantity

Output is complicated. We’ve tried to find ways to assign value to the output of knowledge workers. Our inability to consistently measure output quality makes it hard to find an equation that makes sense for measuring knowledge worker productivity.

The least-innovative approaches simply default to numerical metrics that make little sense. For instance, assessing developers by “lines of code written in an hour” or doctors by “patients treated in an hour” leaves no room for the quality factor. What if another developer writes half as much code as another, but it’s twice as good? What if a doctor sees half the number of patients as another, but with twice the positive outcomes?

How do we measure the output of the brain? If we take the developer example a little further, developers are problem-solvers, not code machines. They spend hours thinking through problems and testing solutions – hours where they’re not producing a single line of code “output.”

2. “What is the task?”

Input is complicated. Think about all the tasks involved in doing your job. There are so many different kinds, right? Knowledge jobs are complex and contain many variables, especially when compared with predictable and repeatable manufacturing processes.

Peter Drucker, a management expert who coined the term “knowledge economy” in 1957, highlighted this complexity with the seemingly simple question, “What is the task?”.

In manual work, the task is always obvious. In knowledge work, that’s rarely the case. Think about how a digital marketer might respond to that question. The answer to “What is the task?” could be anything from attending a meeting to setting up a retargeting campaign and everything in between. A doctor could respond with anything from patient care to paperwork. A salesperson could say driving to networking conference, making calls, or any of a dozen other options.

To complicate matters even more, not all tasks create the same amount of value for a company.

Does responding to an email create as much value as working on a feature article? Most of us would say “no” on the surface. But what if that email builds a relationship with a contact who turns out to be a critical investor down the road?

With so many ill-defined variables in the equation, it’s difficult for managers to scientifically and systematically measure and optimize productivity in the way that Taylor described in 1911.

3. Accounting for the human element

Employees who want to work for you will produce high-quality work in a timely fashion.

If employees don’t want to work for you, no amount of productivity measurement and optimization will solve that core problem.

The entrenched idea of “warfare” between management and employees goes back a long way. Often, the idea of “creating a culture of efficiency” raises the specter of Big Brother and an army of drones beholden to ticking counters on their desktops. Taylor nailed the description of this antagonistic relationship way back in 1911:

It would seem to be so self-evident that maximum prosperity for the employer, coupled with maximum prosperity for the employee, ought to be the two leading objects of management, that even to state this fact should be unnecessary. And yet there is no question that, throughout the industrial world, a large part of the organization of employers, as well as employees, is for war rather than for peace, and that perhaps the majority on either side do not believe that it is possible so to arrange their mutual relations that their interests become identical.

In the manual-work scenario, the company owns the means of production, usually machinery or some other system, and the worker simply iterates tasks within that system. In that scenario, workers can more easily be seen as cogs in the machine. And productivity data can more easily be used as a stick rather than a carrot.

Today, the “self-evident” mutual interests shared by managers and employees is even more, well, self-evident. In the knowledge economy, workers are the means of production – by way of their knowledge and expertise – and the output is the series of creative decisions they make in a day.

This emphasizes a much more symbiotic relationship between companies and employees. When employees are seen as assets, productivity management for team leaders isn’t just about tracking parts installed or time spent on the line. Management now includes taking care of employee satisfaction and building stronger teams.

There’s an entirely different piece to optimizing for productivity: the human element.

Researchers at the University of Michigan discovered that teams and work environments where employees and leaders demonstrated “positive and virtuous” practices scored higher on organizational effectiveness indicators like financial performance, customer satisfaction and productivity.

These “positive and virtuous” practices included:

- showing compassion

- providing support

- being interested in having colleagues as friends

- focusing on meaningful work

- avoiding laying blame and forgiving mistakes

- treating others with respect

- showing gratitude

Many modern workplaces include elements of these “positive” practices explicitly in their values, including Buffer, Zappos and Todoist.

Today, more and more businesses are taking the approach that happy workers leads to a better company. A single-minded focus on output (even if you could reliably measure it) just won’t cut it.

So…Can Team Productivity Be Measured?

Yes, the old “productivity = output divided by input” model fails us on many fronts.

No one has discovered a silver-bullet metric showing managers and company leaders how to measure the true productivity of knowledge workers.

Nevertheless, successful companies have found innovative ways to measure and improve productivity. It just takes a different approach…

Embrace employee autonomy

Management expert and author Peter Drucker writes that the modern knowledge economy “demands that we impose the responsibility for their productivity on the individual knowledge workers themselves. Knowledge Workers have to manage themselves. They have to have autonomy.”

Drucker presents this autonomy as one of the primary reasons why the old manufacturing model falls flat. It’s also one of the primary reasons our ownership of our individual productivity becomes more important.

We all come up against some of the same challenges when trying to measure our own productivity, of course, just writ small. But the “autonomy” Drucker talks about means knowledge workers can – and should – have the opportunity to shape their workdays in ways that they know make them more successful and productive.

Drucker’s primary example of this is when nurses in a hospital were asked what tasks prevented them from being productive. Overwhelmingly, the responses included tasks unrelated to the nurses’ high-value knowledge and skills, such as answering phones and arranging flowers. When those tasks were passed on to non-nurse clerks, within four months patient satisfaction doubled and nurse turnover dropped dramatically.

Automation and delegation free us up to do higher-quality work in the same amount of time, which is a pretty straightforward boost to productivity, even if we can’t necessarily measure the objective quality of that work.

On an individual level, consider what parts of your job require your skills and knowledge, and what parts amount to chores. What can be automated? What can be delegated?

On a team level, managers can do a few things:

- Work with team members to make sure they’re working on tasks that align with their strengths. Help them find ways to maximize the amount of time they’re doing work they find meaningful and minimize time spent on everything else.

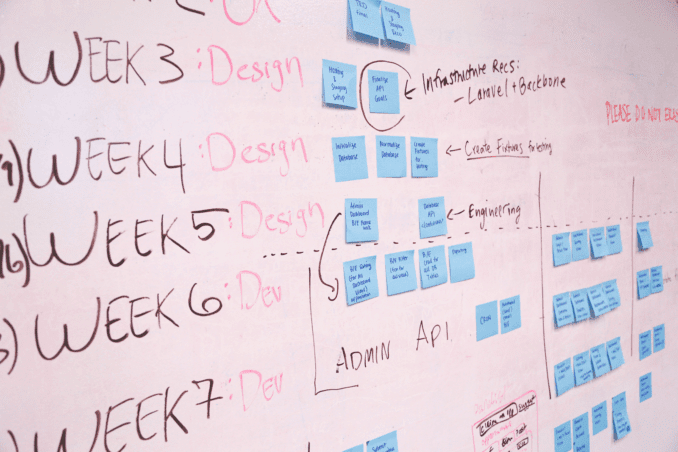

- Think about what you’re measuring when you measure team output. It’s hard to benchmark individual productivity to business goals, but you should be able to tie your teams to things like releasing minimum-viable products on time, patient satisfaction scores, closed leads, etc. Be sure to involve employees in the process of setting these goals.

- Consider creating a standardized yet flexible system of goal-setting. These are designed to fit hard-to-quantify elements into standard formats. Employees themselves are empowered to define what success looks like. These include self-assessments, standardized systems like Agile’s story points system and OKRs.

Creating these kinds of systems gives employees the autonomy to set their goals alongside managers in alignment with company goals. It provides individual, team-wide and company-wide benchmarks, but for the purpose of reaching common goals.

Remember the human element

Personal productivity is at the heart of team productivity. If the key to a high-performing team is to put the right individuals together – individuals with high alignment to your company’s mission and high ownership of their team’s tasks – then the secrets of productivity lie in the secrets of team-building.

In February, an adapted section of Charles Duhigg’s book Smarter Faster Better: The Secrets of Productivity in Life and Business appeared in The New York Times, telling the story of Google’s quest to build the perfect team.

Through research and experimentation, the researchers on Google’s “Project Aristotle” explored the effects of less-tangible factors on team effectiveness and productivity. In an environment like Google – where every detail is tracked, analyzed, optimized and tested – searching for the makeup to the perfect team yielded some decidedly non-technical results.

As it turns out, creating the best team has less to do with combining individually optimized rockstars and more with how “members listen to one another and show sensitivity to feelings and needs,” something Wharton management professor Matthew Bidwell also calls “citizenship behaviors.”

Duhigg expanded on this irony:

Project Aristotle is a reminder that when companies try to optimize everything, it’s sometimes easy to forget that success is often built on experiences – like emotional interactions and complicated conversations and discussions of who we want to be and how our teammates make us feel – that can’t really be optimized.

While Duhigg believes these elements can’t be optimized in the scientific and systematic sense of the word, there may be non-traditional ways to measure and improve them.

You can approach measuring cultural elements like positivity and diversity the same way you approach measuring progress toward your production goals – and you can start by building sustainable organizational habits.

How do you measure and improve team culture?

In The Power of Habit, Duhigg tells the story of how CEO Paul O’Neill completely transformed the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa) by building a sustainable “Keystone Habit” across the entire organization.

On day one, O’Neill announced that worker safety would be Alcoa’s no. 1 priority at every level of the company. No more emphasis on aluminum production or quality control. No focus on “synergy” or discussion of profit margins or markets. Just a company-wide effort to get workplace safety down to zero.

“I intend to make Alcoa the safest company in America,” O’Neil told stunned workers and managers.

He built a system to track workplace injuries. He modeled the leadership behavior that other managers and workers followed. Everyone worked toward the same goal of zero workplace injuries (and, really, who can argue with prioritizing worker safety?).

The transformation spanned the entire company. A culture devoted to safety made workers feel valued and appreciated. Managers focused on a single measurable outcome while also relating to their team on a human level.

Alcoa’s profits soared.

“I knew I had to transform Alcoa,” O’Neill told Duhigg. “But you can’t order people to change. That’s not how the brain works. So I decided I was going to start by focusing on one thing. If I could start disrupting the habits around one thing, it would spread throughout the entire company.”

This idea of the “Keystone Habit,” – a habit that can start a chain reaction of organizational change – can be a key element for managers and leaders looking to strengthen team culture while changing the perception of “productivity tracking” inside their company.

Rather than focusing purely on output, think about measureable outcomes that reinforce a positive, collaborative team culture. If your organizational keystone habit is incredible customer service you might set a goal that measures customer satisfaction. If the habit is team-wide learning you might set a team goal for the number of books read or courses taken.

If you find the right organizational habit and a reliable way to measure it, the rest might just follow as naturally as it did for O’Neill at Alcoa.

The People Puzzle

To sum it up, team productivity might as well be called the “people puzzle” – It’s less about standardizing human behavior to measure output and efficiency, and more about empowering individuals and your team.

If your team experiences productivity issues, your first instinct might be to try to take a deep dive into individual performance. This developer is only creating X lines of code a day! This nurse is only annotating X charts! Half the team is only logging four work hours a day on our time-tracking app!

Your second instinct might be to try to deploy aggressive personal productivity-boosting initiatives.

Just don’t.

Your team’s desire to work more efficiently comes from factors like whether you demonstrate “positive and virtuous” leadership practices and whether they feel like they’re doing valued work that matches their skill-set – not because you required them to start logging their time.

Promote the idea that increased efficiency is, as Taylor said, for “mutual benefit.” Producing higher-quality work more quickly is a win-win. Employees work fewer hours, the company grows and invests back in the employees and workplace, making employees more satisfied and more motivated to continue producing at the same level, and that cycle spirals up and up. You just have to think a little out of the box to define what “productivity” means for your team.

Looking for ways to make teamwork calmer, more organized, and more productive? Learn about Twist by the makers of Todoist.