What would you say if I told you that reading one book can be more valuable than reading fifty? That re-reading something familiar is more valuable than reading something new? What would you say if I told you that you could learn more by reading less?

Information Overload

With 1,500 – 2,000 TV shows aired, 600,000 – 1 million books published, 1 billion active websites & approximately 200 billion tweets posted every year, we live in a world packed with information. In our pockets, a thumb-press away, we carry libraries so vast that even imagining them would be an impossibility.

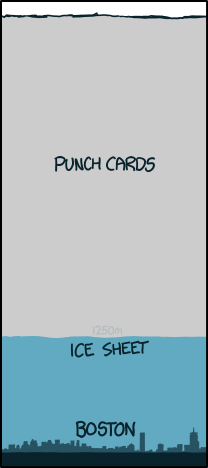

On his website What If?, scientist and cartoonist Randall Munroe attempts to estimate the amount of data stored on Google’s servers. According to his (guesstimated) calculations, if all the company’s data were stored on punch cards which hold 80 characters, 2,000 of which fit into one box, these boxes would cover all of New England 4.5 kilometers deep! And that’s just Google.

Even more impossible than imagining its size is the notion that we should somehow be able to keep current with reading these oceans of information. It’s a crazy idea, yet we still we live in continual attempt. We scan. We skim. We sneak Facebook posts, news feeds and book tidbits into every brief moment. iPhones out while we wait in line or sit at red lights, we gulp all that we can in the fear that we’ll miss something important.

It’s a habit that technology companies are certainly aware of:

- Audible offers listening speeds up to 3X for their audiobooks.

- In addition to the ability to increase listening speed, the podcast app Overcast offers a feature called “Smart Speed” which finds silences in the audio and cuts them out, shaving minutes from every hour.

- Twitter and Snapchat limit you to 140 characters or 10 seconds, respectively.

- Apps like Rooster & Serial Reader deliver small digestible daily chunks of classic books.

- Blinkist sends users the key insights from books (saving them the time of actually reading them).

- Currently, as I write this, the top app in the iPhone app store is Summize in which you “Take a picture of a textbook page or news article and get a summary, concept analysis, keyword analysis or bias analysis in seconds.”

- Spritz is a speed reading app that flashes words or groups of short words in a quick succession across a stationary window which is said to prevent head turning, slowing down and re-reading.

Information is coming at us from all directions at all times. According to Wikipedia’s entry on Information Overload: “A study from 1997 found that 50% of management in Fortune 1000 companies were disrupted by emails more than six times an hour.” This constant pounding of information has only increased dramatically in the 19 years following that survey. In 1997 there were no smartphones. There was no Gmail, social media or text messages. Today, office workers are interrupted, or self-interrupted, every 3 minutes.

Without even picking up a book, we are continually overloaded with information on a daily basis. And the constant exposure to information has real consequences for the way we think and act.

As discussed in a 2008 Scientific American article, willpower and decision making are limited resources. Both require the use of our executive function which is our choice maker. When the executive function becomes exhausted we become less and less capable of making good decisions. At a certain point we’re rendered incapable of making any choice at all.

This is what people mean when they say “I’m so tired. I don’t even want to think about eating.” Information overload leads to a continual feeling of being run ragged. The simple act of swatting away notifications and keeping up with our feeds makes us less motivated to exercise, weaker against the temptations of an unhealthy diet, and overwhelmed when facing decisions.

As much as I advocate for literacy and reading, I don’t think consuming information faster is the solution to the problem. It definitely won’t disperse this continual data smog we live in. In fact, increasing our consumption rate doesn’t mean that we’re learning any more at all.

A Personal Experiment

2015 was my year of brain gluttony. On top of the previously mentioned stream of unending social media posts, emails and text messages, I set myself two fairly insane challenges. The first of which was to watch 300 movies. My second goal was to read 80 books. The whole idea was absurd. And though I would love to say that I failed to achieve both of these goals, something much worse happened: I exceeded them. In 2015, I read 89 books and I watched 355 movies

I quickly learned that at a normal pace there was simply not enough time in a year to accomplish these goals, if I planned on eating, sleeping and working at all. I needed to cheat the system. While I’m not aware of any tricks for watching a movie faster, there are some nasty tricks you can employ to increase the amount of books that you read. In my bag of tricks were:

- the use of audio books

- audio books at double speed

- audiobooks at triple speed

- listening to audiobooks while checking email and surfing the web

- Spritz (the above mention speed reading app)

Now, I have to be very honest. Over the span of the entire year, I feel like I learned very little. I read more and somehow knew less. It seems that the faster the consumption, the lower my comprehension became. I know now that an audiobook at double speed is the exact speed limit of my understanding. At that speed I can sustain comprehension for short periods of time (approximately 10-15 minutes), after which my brain inevitably tires and shuts down by shifting its attention away from the book. Whereas even when paying full attention at triple speed, I still missed at least half of what I was listening to. I just couldn’t grab it all.

I faced the exact same problems when multi-tasking. The brain just simply isn’t capable of reading something on a screen while listening to something else being read. I could only comprehend by narrowing my focus onto one thing and blocking out the other. It seems that, when overloaded, my brain’s response was to shut down or shut out.

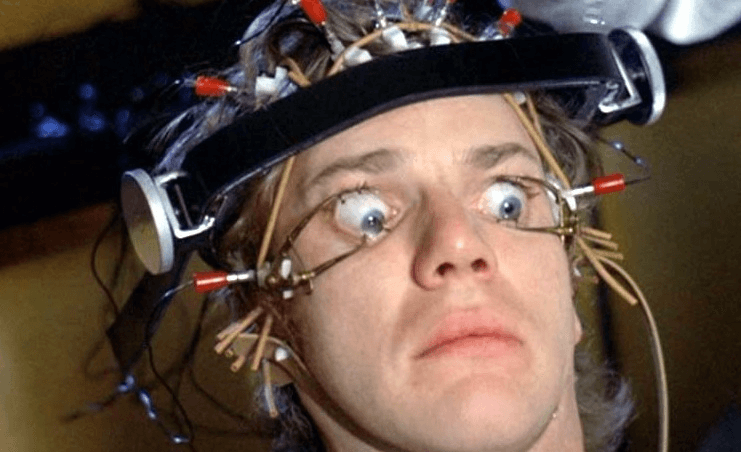

But, of all the things I tried (including reading blogs while listening to an audiobook at double speed) the worst comprehension came with the use of Spritz. Spritz is essentially a text window that flashes one word or several short words in front of your eyes, rather than displaying pages of text for you to scan through. With speeds as high as 700 words per minutes and as low as 100 words per minute, I found that even at it’s slowest, Spritz was not something that I could sustain for an entire book. It just hurt my brain and hurt it almost instantly. I attempted to read portions of Kingsley Amis’s novel “Old Devils” using the app and the portions that I read using Spritz are completely absent from my memory. It’s like I never even read them. All I really remember is a flurry of words flashing in front of me and of those words I was only able to register and comprehend one out of every 30 or 40.

I’ll need to re-read this book again in the future. There’s no way around it, because my comprehension of it has more holes than actual substance. It’s like reading one word from every two lines of text. This level of consumption simply is not learning. You can’t piece anything worthwhile together from such sparse data. I found that using Spritz was less a reading tool and more a form of torture worthy of A Clockwork Orange.

Over the span of 2015, there were many books of which I have the vaguest memories. The experience of listening to each of them remains in only a contextual way. Often I can tell where I was sitting or what the weather was like that day, but of the text itself, I can only recall the most general details. I can tell you what the book was about, I may even be able to relate the details of a few scenes, but I couldn’t begin to tell you what the book meant or what the best parts were. It would be like describing a city that I’ve only driven through.

Remembering vs. Knowing

Our ability to store information occurs in two main forms. First there is “remembering.” Remembering is basic recall, it relies heavily upon context, takes longer to recall and fades faster. For many of us, remembering is what we used to pass algebra and chemistry. We were able to absorb the periodic table and quadratic equations long enough to pass quizzes and tests but we draw complete blanks hearing those terms now.

The other form of learning is what we call “knowing.” Knowing is what occurs when we digest information as truth. It actually becomes a part of us and we can explain it to others. This is the whole purpose of essays, science projects and study groups in school: to stimulate knowing rather than rote memory.

The difference between remembering and knowing is best exemplified in parenting. We can tell a child not to touch a stove and they will remember exactly that, but in most cases it will not prevent them from touching it. They remember you telling them that the stove is hot – they may even be able to tell you where you were standing and what you were wearing – but it will not stop them from touching the stove. They remember but they do not know; they won’t know it until they burn themselves.

In a 2003 study at the University of Leicester, researcher Kate Garland studies the difference between remembering and knowing by comparing reading on a screen with reading on paper. Her research group was given study material from an introductory economics course. Half were asked to read the material on a computer monitor while the other half was given the material in a spiral-bound notebook.

While Garland found that both groups scored equally on comprehension tests, the methods of recall differed drastically. Those who read the information on the computer relied solely upon remembering while “students who read on paper learned the study material more thoroughly more quickly; they did not have to spend a lot of time searching their minds for information from the text, trying to trigger the right memory—they often just knew the answers.”

Though this seems to say a lot about the innate superiority of paper, it is also possible that the differences are dependent upon perception. In other words, paper may not be naturally better for learning, but instead the way that we view paper makes us learn from it more deeply. It’s possibly that we believe paper to be a more permanent medium and that we view online articles as disposable. It is also possible that this valuing may be responsible for how our brain deals with the information obtained from each medium.

When we “remember” something, we call it data, information or facts. When we “know” something we call it knowledge. Knowledge becomes part of who we are as people. We preserve articles into archives which serve as containers for future retrieval, while the purpose of a book is drastically different. The purpose of a book is to inspire growth. A book is meant to become an addition to our sense of self. And it is here that we find our problem with fast reading: When we begin to view books as something to consume and we challenge ourselves to ingest them faster, we begin to see them as data; as simply something to remember. When we stop looking to them for knowledge everything in them becomes temporary.

Deep Reading For Deep Thinking

Beyond the simple shortcomings of basic “remembering”, there are other advantages offered by measured, more careful reading. The need for deeper reading is something we are hearing about more and more in recent decades, going as far as to spark a movement. In 2009, The Slow Book Movement was founded by novelist I. Alexander Olchowski. A movement dedicated to promoting the benefits of deep reading, their core ideas are best expressed by author John Miedema: “If you want the deep experience of a book, if you want to internalize it, to mix an author’s ideas with your own and make it a more personal experience, you have to read it slowly.”

The reasoning here is quite straightforward and requires little scientific evidence to prove itself to the average person. Learning (whether it be remembering or knowing) requires focus. Without paying attention we have difficulty retaining anything, as shown in my foolish attempts to listen to audiobooks while battling back my Gmail inbox. But shallow reading is not something that we do on purpose. It’s something we do because of the fear of missing out on something important, the ugly result of rampant consumerism. The more we consume the more we can be sold.

The website of the speed reading app Spritz claims that beyond flashing words at an accelerated pace, Spritz works by “allowing you to read without the need to move your eyes,” and this is said to save you hours of time. And I have to admit, this all sounds plausible; and it is plausible…to everyone except the experts.

When interviewed by The New Yorker, psychologist Michael Masson stated that, “one of the reasons regressive eye movements occur is to repair comprehension failures.” In studies he has done on speed-reading, Masson learned that the movement of the eyes on the page was essential to comprehension. Without the ability to scan back, the brain barrels forward leaving giant holes in comprehension, while working desperately to piece together an understanding from what little it has gathered. This cripples not only the perception of the passage being read but also the understanding of all future passages which are dependent upon the one being read. A mystery cannot be solved if the detective has missed all of the clues, nor can a novel be understood by reading nothing but the last page. This was exactly my experience with Spritz and Martin Amis’s Old Devils, all I have are unconnected pieces.

We read slowly to ensure that we understand the words in front of us, but we also read slowly with the hope that other thoughts will bleed in. While distracting, inane thoughts will be the first to arrive, with practice these thoughts become more relevant; we will begin to see similarities and differences in other things we’ve read. It is these connections that are the foundation of learning itself. We often confuse learning with the collection of data, but learning is the process of digestion. Learning is what moves something from remembering to knowing. And thisis the deepest form of thinking.

The absorption of one idea is not enough to spark thought. One idea must have another idea to bounce off of. In philosophy, this is referred to as the Hegelian Dialectical Formula. An idea (or thesis) must collide with another idea (antithesis) in order to create a new thought (synthesis). So, by reading in a relaxed manner we not only increase focus, decrease anxiety and stimulate learning; we also create the opportunity for original thought.

Where to Start

How do we begin to develop the practice of reading less and learning more? Well, the first steps are simple but crucial. We must first begin to unlearn the unhealthy habits of the information age. Does this mean throwing away your computer? Smashing your iPhone? Deleting your social media? Giving up on reading online articles (like this one)? No. Of course not. All that we need to begin is the will to hone our habits into practices.

What does that mean? It means setting limitations for yourself. It means turning off notifications and focusing on absorbing what is in front you. It means allowing yourself time to reflect instead of continually dipping into your phone for a fix. It means not rushing yourself to the ends of books; not>challenging yourself to finish more books than your neighbor. It means keeping a notebook next to you while you read and writing down your thoughts. It means re-reading sentences again and again, reasoning them into understanding. It means remembering how to see reading as a way to grow and not as a stat to collect.

It doesn’t matter what device you read from or what content it is that you choose to read, but when you do so, dedicate your time to it. Worry less about what you are missing out on and allow yourself to get lost in thought. Concern yourself less with how much you are reading, and instead invest in how much you are learning>. In the words of Henry David Thoreau, “Books must be read as deliberately and reservedly as they were written.”